How’s the Weather?

The new secretary at the used machine tool company was helping her boss with the annual inventory. Stopping in front of an optical comparator, she asked, “Does this measure atmospheric pressure or something?”

Confused, the business owner replied, “No, it projects a silhouette of a machined part, and we use it to inspect its precision.”

“Then why do we have it listed in our Meteorology Machines section online?”

The boss chuckled and responded, “That’s actually our Metrology section, which is a different word, and it has to do with the science of measurements.” He added, “Though measuring air pressure is a type of metrology, just not the kind that we generally deal with in metalworking.” Later that day he had his website guy change the section title to “Inspection Equipment,” just to avoid confusing any others who might also be new to the field.

The Measure of a Man

Metrology refers to the science of measurement, whether in terms of length, weight, or some other quantifiable unit. It derives from the Greek words “metron,” meaning measurement, and “logos,” denoting a subject of study.

Prehistoric craftsmen wouldn’t have thought in terms of a science of measurement, but they knew that objects had to meet specific size requirements for certain purposes, such as making a spear to an approximate length for ideal use in hunting. As human communities came into existence, setting standards for quantifying capacities of grain, lengths of cloth, or weights of precious metal were essential functions for the prosperity of any economy.

Ancient Egypt established one of the earliest civilization-wide standard of measurements, complete with regular inspection and calibration to ensure that their elaborate building projects were holding to specifications. By the time the world reached the Industrial Revolution, being able to create identical, interchangeable parts became a necessity. Whether items were created by hand or machine, having ways of testing them against a set reference point for accuracy had become a requirement in manufacturing.

Modern metrology is divided into three subfields:

- Scientific Metrology deals with the development of the standards of measurement that are used in society.

- Legal Metrology is focused on the regulatory aspects of measurements and measuring devices, especially in areas that protect both buyers and sellers.

- Industrial Metrology ensures that instruments used for measurements are calibrated correctly and function properly.

Metrology as applied in metalworking falls under the “industrial” category where operators use precision instruments to check produced parts for accuracy so that the machine tools and metal fabrication equipment can be kept in correct alignment to meet required tolerances. By defining standard units of measurement, metrology can be used to validate and verify specifications against those units.

Tools of the Metrology Trade

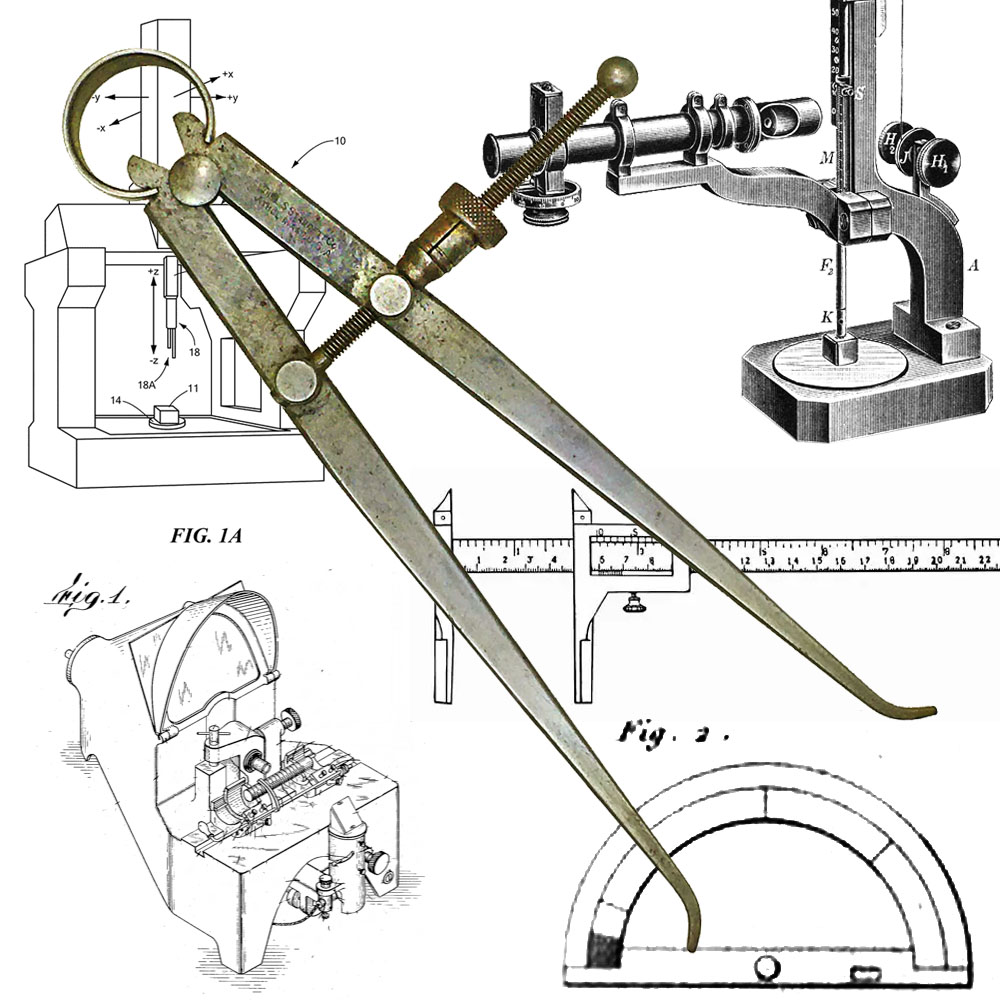

Instruments used in metalworking metrology range from large complex machines down to simple—but highly accurate—straight edge rulers. The smallest measuring unit of a metrology tool is called a “least count,” with the least count of a ruler being perhaps 1 mm and the least count of a micrometer around 0.01 mm. Some of the common inspection and testing devices include:

- 3D Scanner. Optically based 3D scanners can be moved around an item to collect digital data that can be rendered on a computer to display a moveable model of the item that shows accurate dimensions from every side.

- Air Gauge. An air gauge shoots pressurized air at an object and has sensors that detect the rate at which it returns to give a measurement of the dimensions of the object.

- Angle Plate. An angle plate is used for clamping a workpiece in a vertical position for layout, tooling, and machining, as well as being a vertical reference for inspection.

- Bed Plate. Also known as a base plate, clamping plate, floor plate, or test bed, a bed plate is used as a ridged surface for assembly, inspection, layout, marking and testing.

- Bevel Protractor. See Protractor.

- Bore Gauge. A bore gauge is used to accurately measure the inner diameter of holes in precision machined components.

- Caliper. A caliper is a device used to measure a dimension on an object. Calipers have been in use since at least the sixth century BC, and while analog versions are still widely used, digital calipers are often chosen for their accuracy and ease of operation. A common type of caliper is the vernier caliper, which has a large set of moveable jaws for measuring external dimensions, a smaller set for measuring internal dimensions of a hollow or hole, and a sliding vernier scale that moves along the longer main scale.

- CMM. An abbreviation for coordinate measuring machine.

- Comparator. A shortened term usually referring to an optical comparator.

- Computed Tomography Scanner. Usually known by the shorter CT scanner (and often CAT scanner, for computed axial tomography), a computed tomography scanner uses an x-ray procedure to create cross-sectional images with the help of computer processing. A 3D model can be created using the CT images, but unlike the standard 3D optical scans, they can show the inner details of the object.

- Contour Comparator. Another name for an optical comparator.

- Contour Gauge. See Profile Gauge.

- Coordinate Measuring Machine. A coordinate measuring machine, or CMM for short, is a machine that senses distinct points on the surface of an object with a probe using light, touch, a laser, or some other means. The data collected is assembled to measure the geometry of the object. One type of a portable CMM is called a laser scanning arm.

- CT Scanner or CAT Scanner. Abbreviations for computed tomography scanner.

- Depth Gauge, Depth Indicator, Depth Micrometer. Depth gauges and depth micrometers are used to accurately measure the depth of a point from the surface of an object.

- Dial Gauge. Also called a dial indicator, a dial gauge is a widely used type of mechanical comparator. The two most common types are the plunger dial gauge and the level dial gauge. A plunger dial gauge is usually referred to as simply a “dial gauge” and measures the amount its plunger or spindle is pushed up inside its casing. A level dial gauge is often called a “test indicator” and measures the amount its lever or probe moves in a swinging arc.

- Engineer’s Spirit Level. See Level.

- Engineering Square. Another name for a machinist square.

- External Micrometer. See Micrometer.

- Feeler Gauge. A feeler gauge is a thin blade of a specific thickness used to measure the clearance (narrow gap) between two parallel flat surfaces. Several feeler gauges of different thicknesses will often be attached together in a framework resembling a pocketknife.

- Gauge Block. Gauge blocks are precision ground and lapped blocks of metal or ceramic. Each block has a specific thickness and is used for measuring lengths or heights, either individually or stacked with other gauge blocks.

- Go/No-Go Gauge. The oddly named go/no-go gauges are inspection devices with dual measurements, one section being a “go” measurement that should fit the finished workpiece, the other being a “no-go” measurement that shouldn’t fit it. A go/no-go gauge is used to test a part to make sure that it is within designated tolerances. A plug gauge is one type of go/no-go gauge. Plug gauges have two ends, one “go” and the other “no go” and are used by—as the name implies—either plugging or screwing them into a part to test its tolerance. A snap gauge is another type of go/no-go gauge. It has two pairs of jaws, with the first set to the upper limit of the part and the second set to the lower limit. A part machined to the correct tolerance will fit the first but not the second set of jaws. Two pin gauges can also be used in tandem to form a go/no-go gauge (see also Pin Gauge).

- Granite Inspection Table. See Surface Plate.

- Height Gauge. Used for vertical measurement, a height gauge has a scale that extends upward from a reference surface, such as a precisely ground base. A vernier height gauge has a sliding vernier scale on the longer main scale. Height gauges can be analog or digital.

- Indicator. The word indicator refers to any instrument that is used to accurately measure a small distance and amplify the results in a way to make them easily readable to a craftsman, such as through a scale, dial, or digital display. The word is often interchangeable with “gauge” (for example, a dial indicator and a dial gauge are synonymous).

- Inside Micrometer. See Micrometer.

- Lapping Plate. A lapping plate is used for accurate hand lapping (rubbing two surfaces together with an abrasive between them) to achieve a perfectly smooth, flat exterior on a workpiece.

- Laser Scanning Arm. A portable type of coordinate measuring machine.

- Level. Also called a “spirit level” because of the mineral spirit solution inside its bubble gauges, a level is used to check the levelness of any surface in relationship to the horizontal plane of the earth’s surface. A simple device, it indicates a level surface when the air bubble is exactly centered inside the clear vial of liquid that serves as its gauge.

- Lever Dial Gauge. See Dial Gauge.

- Machinist Square. Also known as an engineer’s square, a machinist square is used to confirm right angles.

- Machinist’s Level. See Level.

- Magnetic V-Block. See V-Block.

- Measuring Tape. See Tape Measure.

- Micrometer. A micrometer is a precision measuring tool that is generally more accurate than a vernier caliper. An outside micrometer, also known as an external micrometer, often resembles a C-clamp and can measure the outside diameter of a circular object. An inside micrometer is used to measure the internal diameters of holes, such as hollow pipe. Micrometers can be analog or digital.

- Optical Comparator. A magnified silhouette of a part is projected on the screen of an optical comparator and inspected to verify if its geometry and dimensions are within specifications.

- Outside Micrometer. See Micrometer.

- Pin Gauge. A pin gauge is used to inspect the features of a bored hole, such as straightness. It doesn’t check a measurement so much as whether the hole is within tolerance. Two pin gauges can be used in combination as a “go/no-go gauge” to see if a part is either acceptable or unacceptable (see also Go/No-Go Gauge).

- Plug Gauge. See Go/No-Go Gauge.

- Plunger Dial Gauge. See Dial Gauge.

- Profile Gauge. Also called a contour gauge, a profile gauge uses a set of tightly grouped parallel pins that can independently move within a framework to make a cross-sectional impression of a surface when the pins are pushed up against it. The profile that has been captured in the arrangement of the pins can then be copied to another surface.

- Profile Projector. Another name for an optical comparator.

- Profilometer. See Surface Roughness Tester.

- Protractor. Protractors are tools for measuring angles. A simple protractor is a half-circle of transparent plastic or glass with marked angles that can be placed over a workpiece or layout. A bevel protractor is a metal tool with a straight-edge arm that can pivot away from the main arm or base and measure an angle between two sides of a workpiece. Vernier scales are sometimes incorporated into a bevel protractor to allow more precise readings.

- Radius Gauge. Radius gauges are blades that can measure the radius of an object. Several different size radius gauges will often be attached together in a framework resembling a Swiss Army Knife, with convex radii blades on one side and concave radii blades on the other.

- Right Angle. A right angle is a device, often made of cast iron, that has two precise surfaces set at a right angle to each other. It is used to check squareness and as a vertical reference for inspection.

- Roughness Gauge. See Surface Roughness Tester.

- Ruler. See Steel Scale.

- Screw Gauge. A screw gauge is used to measure the diameter of a thin wire or the width of a metal sheet.

- Snap gauge. See Go/No-Go Gauge.

- Square. See Machinist Square.

- Steel Scale. A steel scale is a precise metal ruler, usually with inches and millimeters measured out on opposite sides.

- Straightedge. See Steel Scale.

- Surface Plate. A surface plate or surface table is a smooth, flat surface used to check flatness and squareness of objects and as a reference point for vertical measurements. While they were originally created out of metal—and cast-iron surface plates are still in use today—granite surface plates came into widespread use during World War II due to metal shortages and remain a popular style today. Many metalworkers prefer granite surface plates because they don’t rust or corrode, have a non-glaring surface, and aren’t magnetic.

- Surface Roughness Tester. A surface roughness tester physically probes or digitally scans the surface of an object to determine its roughness. The measurements are given as one of two units, either Ra, the average roughness of a surface based on a measurement of all “peaks” and “valleys,” or Rz, the difference between the tallest and deepest points on the surface. One type of surface roughness tester is a profilometer, which can determine specifications such as curvature, flatness, and step by analyzing the topography of the part’s surface.

- Tape Measure. A good, old-fashioned measuring tape is used for determining long distances or diameters of round objects. Metrology standards set by NIST (the National Institute of Standards and Technology) state that a 6' long tape measure used for commercial purposes must be accurate to within 1/32".

- Test Indicator. Another name for a level dial gauge (see Dial Gauge).

- Thread Measuring Tools. Devices for measuring threads cut into a shaft include thread micrometers and thread pitch gauges.

- Universal Measuring Machine. Universal measuring machines (UMM) were the predecessors for coordinate measuring machines (CMM) and are not readily available today (though custom-built models are still ordered by metrology labs). An extremely accurate machine, a UMM operates slowly and requires a highly trained operator to use it. A modern CMM can rapidly inspect absolute points on an object, but must calculate geometric relationships, whereas a UMM can carefully measure those relationships, and do so without moving linear axes.

- V-Block. Sometimes spelled out as “Vee block,” a V-block resembles a short press brake V-die with a V-shaped channel cut into the top. They are used for checking the roundness of cylindrical workpieces, as well as accurately marking centers. Some have clamps to hold down the part to the V-block while they are being worked on, and others are fabricated with a large hole in the middle with a magnetic rod that can be switched into position to secure a ferrous part in place.

Other metrology devices for measuring things like temperature or electric circuits are also often used by metalworkers.

The Significance of Metrology to Ordinary People

The application of metrology is essential in society, allowing a higher, more accurate standard to be followed in metalworking and other manufacturing. This, in turn, gives consumers a greater sense of confidence in the machines, food, medicine, and other products that they purchase or otherwise interact with.

Metrology isn’t just for metalworkers and scientists—measuring tools are used in everyday life by all people, whether in filling up a gas tank, setting a timer for the laundry, or leveling out a measuring cup while cooking. (If you happen to be reading this article on a mobile device, then you are likely keeping an eye on your battery life indicator, another metrology gauge.) Other common metrology devices include:

- Clock.

- Dipstick.

- GPS.

- Medication Measurements.

- Power Meter.

- Scales.

- Speedometer.

- Thermostat.

- Timer on a Video.

Metrology may not be a term brought up frequently at social gatherings, but it is a critical component of society and should be of particular concern to anyone in the metalworking field where it needs to be constantly applied.